BY YAYOI LENA WINFREY for WEEKLY VOLCANO 2/20/26 |

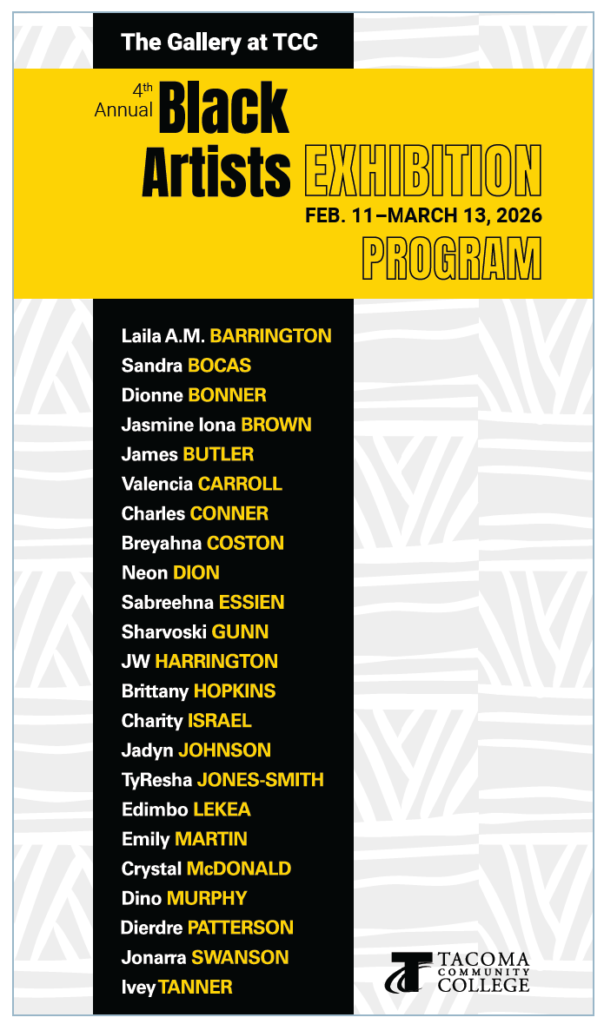

Tucked between several large buildings on the north end of Tacoma Community College’s campus lies a lovely little art gallery. Managed by art history professor Dr. Jennifer Olson, the cozy room is substantial enough to display works by 23 artists featured in the Black History Month exhibit.

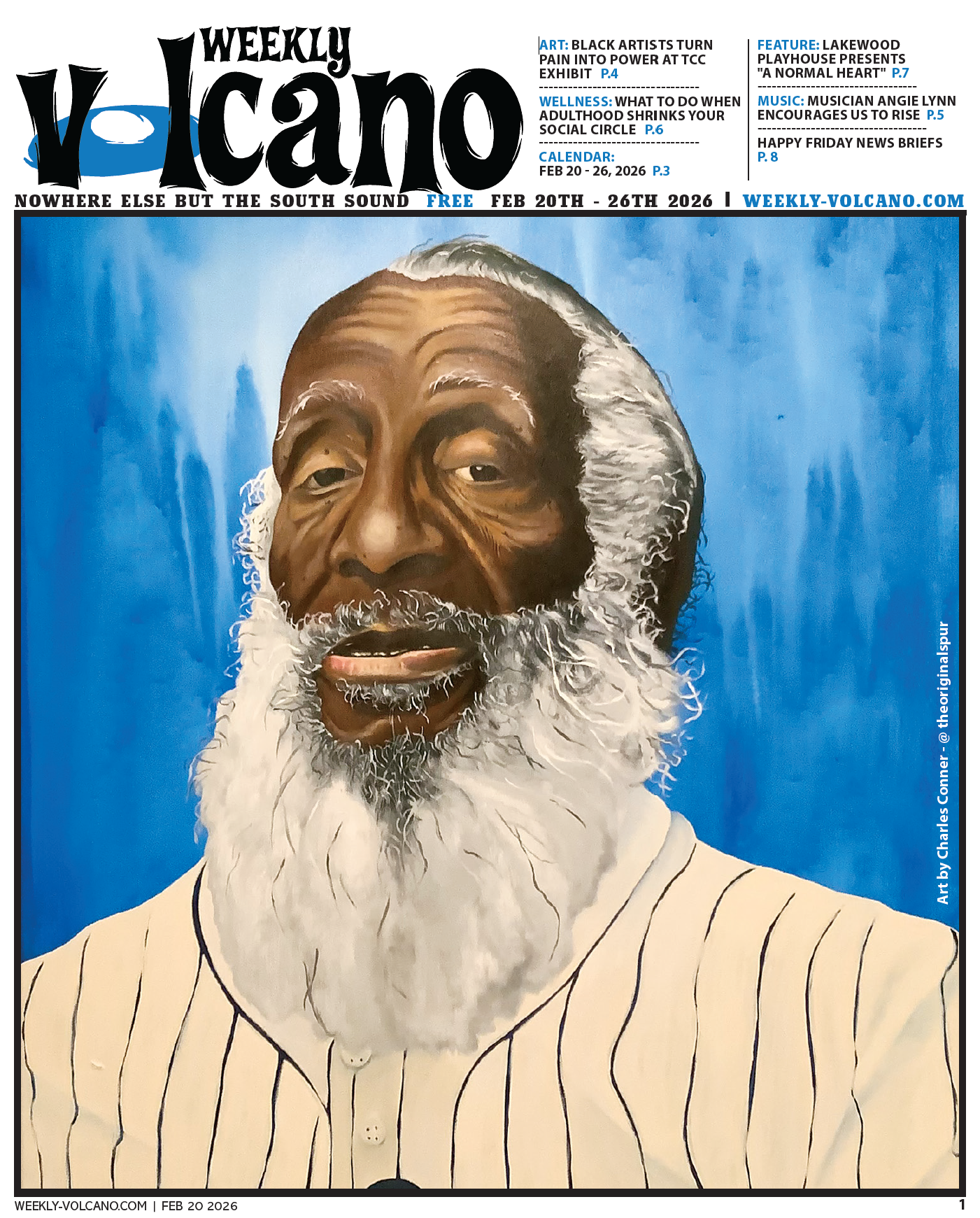

Participating artist Charles Conner whose work is featured on the cover of this newspaper says he hopes that the time viewers spend in the space opens them up to those emotions they haven’t tapped into, and allows them to be more curious. “I hope that the public will gain a sense of wonder, a sense of community, a sense of artistry, and willingness to engage,” he says. “Just see us and appreciate the love, passion, and care we can bring to the world that seems to relish in misery.”

Conner, aka “The Original Spur,” is a talented painter. He acquired the nickname from his great-grandmother, who would call him “spur head” due to his hard-headedness and inability to listen. It was also “on account of my nappy hair,” he adds. Born and raised in Mississippi, Conner also grew up in Alabama. He began drawing at four and enjoyed creating video games and comic-book characters throughout his childhood.

At 17, Conner joined the Army to improve his financial status. Called to active duty in Iraq, he was forced to quit college. By the time he left the military, Conner found himself fighting a different kind of battle, PTSD. But he soon discovered that making art helped him overcome his mental hardships.

“Art is my therapy,” says Conner, adding, “Creating helps me focus, takes those things that may disrupt my peace and allows me to channel it in a creative manner. As artists, we spend a lot of time alone and in our heads,” he continues, “so having my art to lean on when those days seem suffocating is paramount.” Elaborating, he adds, “It’s the task of researching, formulating, storyboarding, and applying that brings a great sense of accomplishment, making it all worthwhile.”

Conner says that his art is influenced by his environment. “I try to create art that reflects what I grew up with, what I saw, and what matters to me,” he explains. “I think that when you move to a place that doesn’t have the same dynamics, you have to find your people and things that keep you grounded in your culture when there is a lack of it in your surroundings,” he says. “It’s an amazing feeling seeing Black culture on canvas.”

His acrylic painting of comedian and activist Dick Gregory is titled “Spirit of St. Louis.” “I wanted to showcase some heritage and lineage of his place of birth by putting him in the St. Louis Stars Negro League baseball jersey,” Conner explains, “I love doing pieces in duality, multiple meanings, layers that bring it all together in one amazing story.”

Ivey Tanner is another military veteran who also uses art to heal from PTSD. Growing up in Dayton, Ohio, she feels, was a restrictive experience because of its limited number of African Americans. “Living there created a need in me to connect with that side of me,” she says, adding that Dayton was a typical small Midwest city “juxtaposed between wanting to be a thriving cultural metropolis and… cows.”

Attending performing arts schools and growing up listening to early hip-hop impacted Tanner artistically. But as an Army veteran, she grappled with combat-related PTSD following 20 years of active-duty service. Then she discovered that sculpting with clay, ceramics, and mixed media helped her tremendously.

“When I’m working with clay, everything else fades into the background,” she explains, “I breathe differently. My nervous system settles. Working with clay feels ancestral to me. It feels like something my hands have known before. When I’m creating, I’m transported to a space of being, not reacting, not surviving, not carrying trauma… just being. There’s both surrender and structure in it. As a vet with PTSD, I need that. A place to release and exist. A place that asks for patience and presence.”

Tanner’s series of ceramic figures titled “The Daughters of Phoebe” was created in honor of her great-great-grandmother. “I first learned about Phoebe through a family lineage book my Aunt Annie made for me after my mother passed away,” she says, “That book traced our bloodline back to her.” Tanner was later able to confirm records through genealogy research and AncestryDNA tests. But other than family oral history, not a lot is known about Phoebe.

“She came to me in pieces of visions and dreams,” Tanner reveals, “Some of them were so beautiful, and some of them so gut-wrenching and painful.” There were also times that Tanner felt that her late great-great-grandmother didn’t want her life exposed to the public.

“But once I began sculpting her story in clay, something shifted,” says Tanner, “Her countenance, the one I felt, softened. It was as if her energy breathed ‘thank you.’ That’s when I understood; she didn’t want to remain hidden. She wanted to be remembered.” By honoring Phoebe, Tanner says she is “giving visibility to the countless Black women whose lives were never fully recorded.”

To her, the Black Artists Exhibition represents more than just art. “I would love for people to understand that Black art is not just a commodity or decoration,” she explains. “It’s medicine. It’s memory. It’s resilience. It’s grief and joy existing at the same time. It’s allowed to have all the meanings or none of them.” She adds that Black art is meant to be experienced for the sake of Black artists and “for the sake of the public viewing it.”

4th Annual Black Artists Exhibition, The Gallery at TCC, February 11–March 13